Reflection on Software Engineering

06 May 2025A Culminating Experience in Software Engineering

Introduction

Software engineering to me is much more than just programming and coding the written product, but it is about creating maintainable, scalable, and collaborative systems. Two foundational aspects that deeply influence the success of any software project are design patterns and Agile project management, or to be more specific, working in parallel with teammates. In our recent project, where we built a web-based meal tracking application, I witnessed firsthand how the new idea of coordination for all teammates created many inconsistencies with how we would solve issues and inevitably solve issues

Design Patterns

Design patterns are established solutions to common software design problems. They help standardize architecture across a codebase and provide a common ground for all of the developers in a team. However, design patterns only serve their purpose if all team members are in on their implementation. In our project, we encountered significant issues communicating which design patterns we were following, mainly the structure and reuse of components in React, structures in the backend, or the organization of shared utilities like the dbactions. Without a formal and consistent briefing, teammates often made assumptions about how pages, components, or database layers were linked, or there were repetitive uses of components. This led to duplicated logic, incompatible props between components, and an overall fragile architecture that became harder to refactor as features grew.

Agile Practices

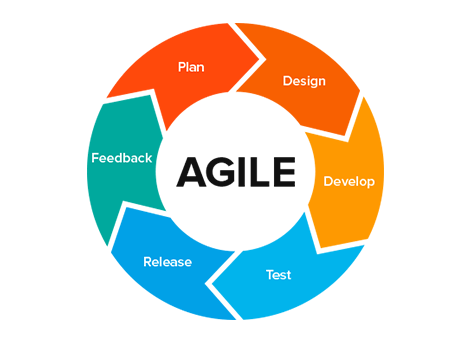

Agile project management emphasizes iterative development, adaptability, and frequent communication. While Agile encourages flexibility, it still relies on strong communication channels and shared understanding of the project’s direction. In theory, Agile ceremonies like stand-ups, sprint planning, and retrospectives should serve as natural touchpoints for aligning on design choices. But in our case, most meetings were remote and fast-paced. When we did meet in person, we often forgot or assumed someone else had already covered discussions on foundational patterns or component hierarchies. This left gaps in understanding that were only discovered during integration or debugging phases, costing us time and momentum.

Lessons Learned

Looking back, our project would have greatly benefited from an early design architecture briefing, even in a lightweight form. A shared diagram or even a wiki page outlining the component tree, API design, and key pattern conventions (e.g., hooks for data fetching, layout wrappers for shared UI) could have served as a source of truth. In Agile terms, this would align with the principle of “just enough documentation,” not overburdening the team but enabling shared understanding.

Conclusion

Ultimately, this experience taught me that design patterns and Agile are not in opposition but must work hand in hand. Agile gives us the tools to collaborate quickly, but design patterns ensure we build cohesively. Without shared design alignment, Agile can drift into chaos. Going forward, I believe that every project needs an intentional phase of design alignment, especially when teams are distributed or meeting asynchronously.

This essay was grammar checked with ChatGPT.